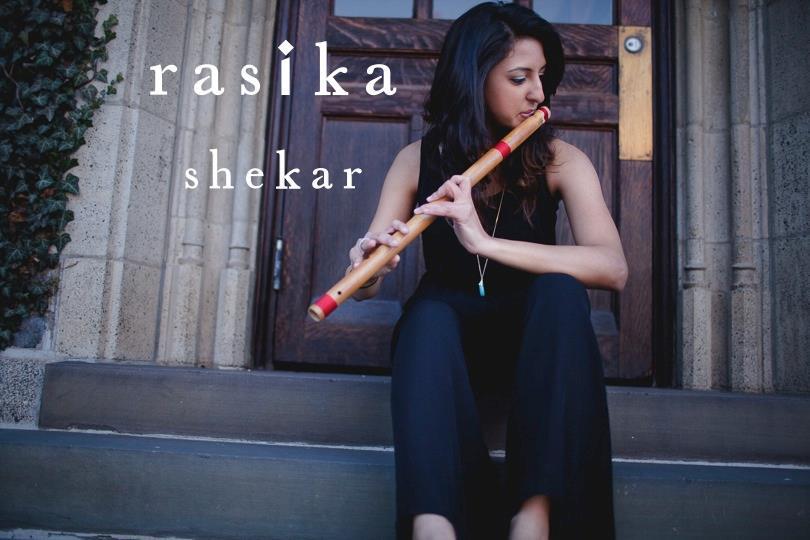

It’s been a few decades since flautists J.A. Jayanth and Rasika Shekar first took the stage. Bamboo flute in hand, they presented the music they knew best, Carnatic music, to the adulations of friends, family, relatives, and well- wishers that would soon become some of their most avid of rasikas. They called it the ‘pullankuzhal,’ or Carnatic flute, and equipped with this seemingly small instrument, they wove melodies in a variety of ragas, talas, and rasas.

Pretty soon, the young artists found themselves drawn to sounds from Northern India and with that, different

types of flutes all together.

“The world of ghazals really fascinated me – the way in which Hindustani artists express emotion and poetry in ghazals, specifically. I was hooked,” Rasika smiles. A vocalist born and bred in the U.S. with generations of

musicians before her, she found the system helpful in improving voice culture. Soon enough, the emotive quality led her to the way she views music now – a large pool of different vocabularies, each a different ornament used to display the same, artistic thought process.

Across the globe, Jayanth, a product of equally-impressive lineage, found himself veering towards a similar system. Exposed to the distinct tones of the bansuri – a longer, bamboo-crafted flute used primarily in Hindustani music – through the works of Pt. Hariprasad Chaurasia and Pt. Ronu Majumdar, he found himself enamored by the deep, rich tone of the bass flute.

“I was in my teens when my flutemaker came home and, as I can vividly remember, I asked him to make me a direct double bass, D# flute. Flutemakers down South weren’t acquainted with this type of flute whatsoever, so making it was a process,” he laughs. Eventually, it’s become a mainstay in many of his Carnatic concerts today, so much so that photographers wait until the end just to capture him playing an Aahir Bhairav on this rare instrument.

Their journeys couldn’t be more different. While Jayanth is known primarily as a Carnatic flautist, the traditional kutcheri his medium through which he expresses his music, Rasika has found her footing as a collaborator. Her involvement with trio Shankar-Ehsaan-Loy is probably the most notable, with a jugalbandhi video of her mimicking Shankar’s vocalizations on the flute continuing to go viral on global social media.

“The minute I started playing jazz, for instance, or simply collaborating with other artists and ensembles, I became sensitive to how my instrument could respond to the occurrences around me. All of a sudden, it became about musical conversation. Is this translating what I’d like to convey?” she questions.

A valid question to ask, Jayanth notes, for interactions abroad and careful study of other flutes such as the Japanese shakuhachi have led him to his own path of inquisition.

“I’d call it an endless quest, to be honest – the more you master your instrument, the more curious you become. And the more you investigate, the more you realize how far away you are from the benchmark you’re aiming to reach,” he explains. It’s a quest that’s led him to experiment with carbon fiber and glass, among a host of other variations.

And yet, after all is said and done, both artists say that they can’t help but revisit their own collections of bamboo

flutes with renewed vigor.

“The bamboo is best suited to the type of music we represent,” Jayanth says simply. This acknowledgement seems

to be what carries the two forward as they continue to innovate with flutes of different lengths, breadths, and

tonal qualities.

Of course, this begs the question, what exactly are they searching for?

“Right now, it’s simply about self-expression,” Rasika tells us. “What is the truth behind it, and how does the

ornamentation and technique of each genre feed into the greater picture of expressing oneself musically?”