A common sentiment in our data-driven, validation-oriented, screen-first world is that we are untouched by the barriers of language. The world is quickly moving towards homogeneity, facilitated by a seemingly universal desire for more likes, hearts, hashtags and acknowledgement.

As our loneliness becomes more emphatic and we scream our collective isolation on Twitter, a band in Tripura stokes a sense of community emerging from simultaneous conflict and safety : memory.

When 33 year old Rumio Debbarma returned to Agartala, he found himself staring into his own history. He discovered that his mother wrote poems in Kokborok, their native tongue and the language spoken by Tripura’s indigenous population.

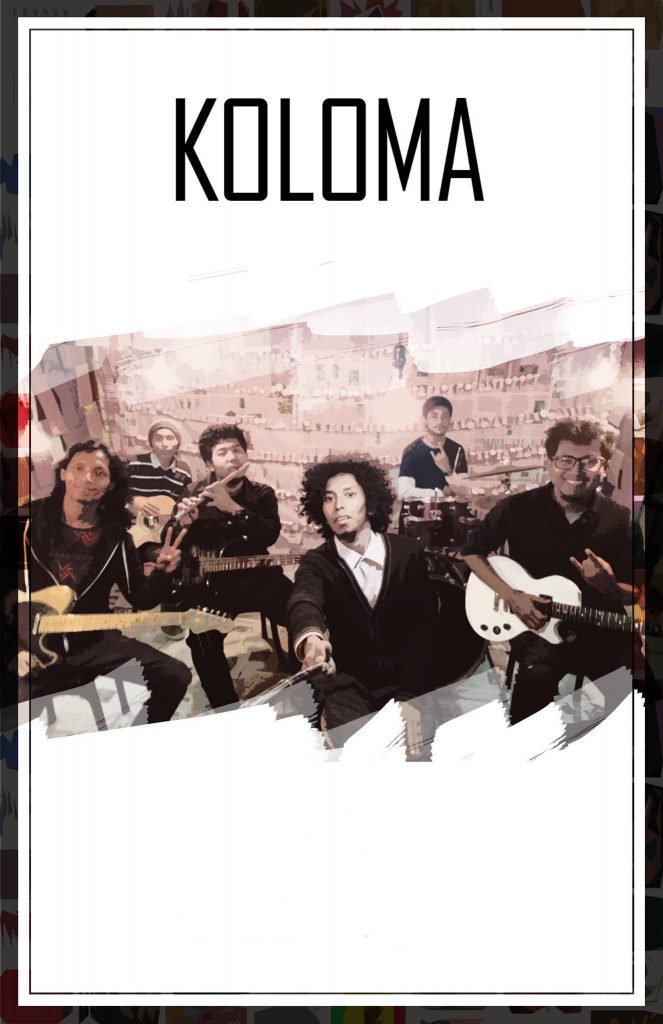

Mother and son now collaborate, crafting words at the centre of Koloma’s artistry. The five member group touches on folk, rock, fusion and give life to tradition. “We want to preserve our language and the way our folk artists sing,” says Rumio.

The band hails from the Borok people, and have named themselves after the original script of Kokborok. No longer in popular use, it has given way to Bengali or Roman scripts which are the now-prevalent modes of writing Kokborok.

Despite being the language of the state’s native inhabitants, not only is Kokborok the second official language of the state (Bengali the first), but is quickly eroding into extinction. Faced with this erasure, Debbarma and his compatriots (all of whom share the same surname) try to preserve the tongue that gave them their first words .

Rumio’s first composition was a 2012 adaptation of his mother’s poem ‘Masing Jora’. Since then, the band had created songs combining magnetic melody and unfamiliar words. Listening to them is akin to deciphering a dream while awake. The sounds are intimate; they have charmed you before. The instruments shimmer in expected ways, hailing bliss inherent in well-worn wonders. Expect the comfort of walking the path back to a happy home.

However, Koloma’s purpose is found in words. Listening to Kokborok is not about comprehending meaning, but realising that entire identities are built around language. If you feel alienated by their lyricism, the point has been made. Splice that sense of disconnect with the everyday experiences of people from Koloma’s world. What must it feel like to wake up and remember that the first words you ever spoke are being relegated to dusty history?

The very act of singing with words half-faded from Tripura’s memory is a revolution. It is taking a stand for one’s own relevance. Weaponizing the warmth borne of self-expression, Koloma’s art is confessional at its core.

The songs explore romance, passing seasons, brotherhood, unity, the state’s inaugural culture, folk tales, snippets of tribal history. In their latest album “Kothoma”, they primarily deliberate upon their own cultural matrix.

Naturally, Koloma’s music is not for mass consumption. Sound, sentiment and word coalesce as an act of personal rumination. Their bid to preserve Kokborok is equivalent to preserving the identity of an entire people.

As easy as it is to qualify anything borderline decent as “soulful”, you can actually hear soul quiver in Koloma. Focus must stay unequivocally on language, and it is hard to imagine that such volumes being communicated with words that are, for most people outside Tripura, foreign.

Even though Tripura does not afford much opportunity for indie music to thrive, Koloma’s music has come to be recognised as unmatchable. How often does a band act as both artist and chronicler? They seek to remind forthcoming generations of the complex tapestry of Borok history – delight, trauma and wonder.

Taking a moment to listen to Koloma is worthwhile. Taking many moments to listen is to know closeness and distance, empathy and astonishment. Take many moments.