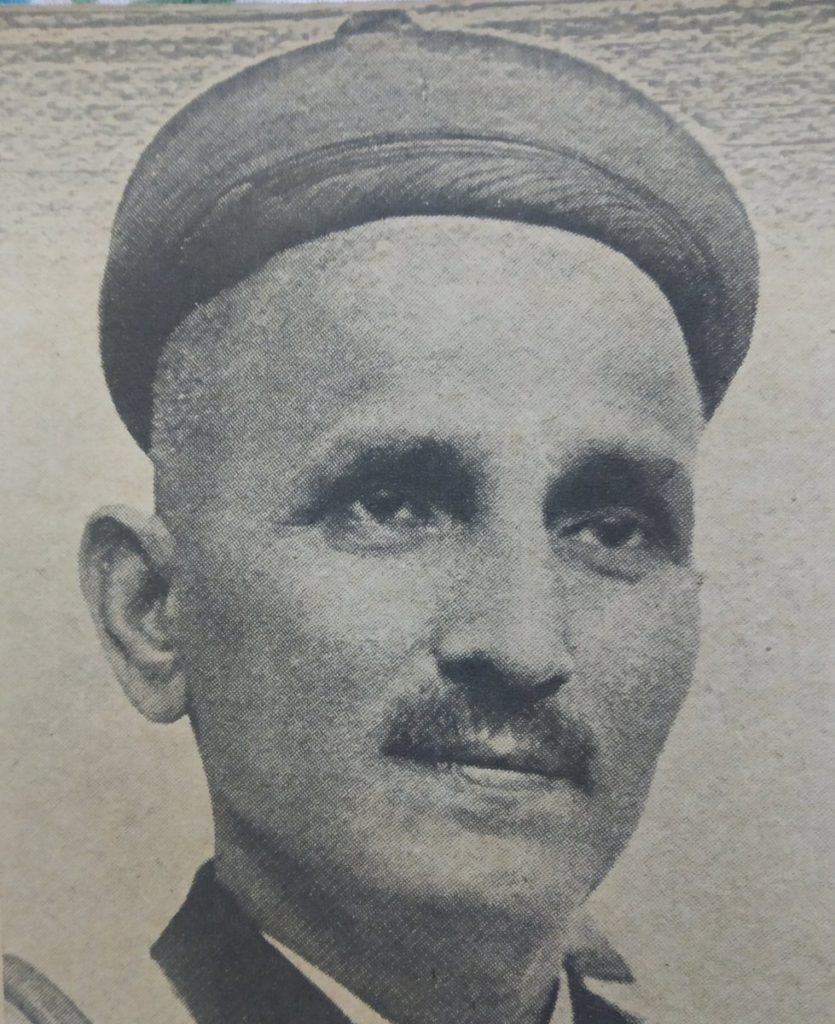

THE MAN WHO PUT INDIAN MUSIC TO PAPER – Score Short Reads

The passion for quality art forms has been universal and timeless. Even after centuries of erosion many legends are still afresh and remembered by the masses. This is one such story of an incredible man, a devoted music researcher, and a true lover of music.

Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande was a practicing lawyer with a tremendous zeal for our classical music. He would soon take off and travel the length and breadth of the country with his mission to bring Indian music to the world.

Since most of the traditional system of music propagation involved oral practices where a disciple would be trained from her Guru and then propagate it further; there remained hardly any available text for teaching and propagating this knowledge across boundaries and timelines.

Though there were individual efforts at preserving the musical culture of the gharanas at some nawaabi durbars, there remained no unification and consolidation of the information.

Bhatkhande, traveled to far southern and northern Indian provinces to meet various musicians and their gurus. He would often ask them to share their in-depth understanding of the grammar and the compositional virtues of the music they were masters in.

Owing to the cultural practices, many would often refuse and delay the process of research for Bhatkhande. Nevertheless, he pursued this expedition for knowledge across the different musical reservoirs of the country.

He traveled to Madras to meet Thiruvottiyur Tyagier and Tachur Singaracharya. He traveled to Ramanathapuram to meet Srinivasa Iyengar. His extensive tours fetched manuscripts like the Chaturdandi Prakasika of Venkatamakhin and the Svaramelakalanidhi of Ramamatya.

His understanding of the music, the studies, and research would yield one of the most standardized texts on music- Hindustani Sangeet Paddhathi. He would also define the system of thaats. He devised this to arrange the structure of both the ragas and the singing style of the Carnatic music. He reportedly created at least 23 short pamphlets to testify and put forward the findings of his musical research.

This would later become important chronicles of study for scholars through universities of music. The Swaramalika, Geet Malika, Grantha sangeetam, Bhavi Sangeetam, Lakshya Sangeetam and Abhinavaragamanjari, and the Abhinavatalamanjari are some of his notable works.

His inspiration would channel many young minds and artists into pursuing the expedition of knowledge in places like Gwalior, Lucknow, Nagpur, Bombay and Baroda.

Bhatkhande found many obstacles on his path, but he had also found his patron in the rulers, or nawabs of the time. Importantly, there was a Maratha ruler, Sayajirao in Baroda, Gujarat who had invited him and Vishnu Digambar Paluskar to his court.

The ruler owing to his refined taste in music and performing arts, ordered Bhatkhande to build up an academic curriculum for his Gayan Shala. He was reportedly asked for creating a system of gradation and evaluation for both the scholars and the artists of the time.

Bhatkhande capitalized on this association and came back with more interesting ideas. One of the most important developments of this time would be the suggestion for a National level music conference.

As per the suggestion of this devoted musical researcher, Sayajirao would organize the grandest musical conference for the first time ever. It hosted different artists and scholars from across the various genres of music in the country.

All of a sudden, there were about 400 talented musicians at one place singing to the glory of Indian classical music. Bhatkhande’s name would go into history forever, and scholars would learn and try to emulate his love for music, for many generations to come.

The Marris College of Lucknow, set up by the Avadhi Taluqdar, Rai Umanath Bali, would go onto become the much-celebrated Bhatkhande Institute, in 1948. This would be a sought after place for academic research and studies of music.

His efforts would eventually lead to a major figure of 1800 compositions of various singing styles across the sub-continent. Thus many crowning jewels rusting within the confines of the temples and courts were finally saved from being lost in oblivion forever.